Summary

Martin Karl Hellinger (17 July 1904 – 13 August 1988) was a German Nazi dentist who in 1943 was assigned to work at the concentration camp for women at Ravensbrück, with the duty of removing dental gold from those killed at the camp.

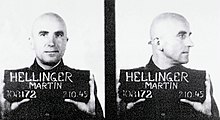

Dr. Martin Karl Hellinger | |

|---|---|

Hellinger on 2 October 1945 | |

| Born | 17 July 1904 |

| Died | 13 August 1988 (aged 84) |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | War crimes |

| Trial | Hamburg Ravensbrück trials |

| Criminal penalty | 15 years imprisonment |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1933–45 |

| Rank | Hauptsturmführer |

At the first Ravensbrück trial, beginning in 1946, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison. He was released in 1954 and given funds by the West German government to re-establish a dental practice. Details of his later life are unknown.

Early life edit

Career edit

Hellinger joined the Schutzstaffel (SS) in 1933.[2] He served at Sachsenhausen in 1941 and Flossenbürg concentration camp between 1941 and 1942. From spring of 1943 to 1944, he was at Ravensbrück when he was promoted to Hauptsturmführer.[2]

Orders to gather irreparable[clarification needed] gold teeth from living people and extract the gold from the mouths of corpses were given by the SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, on 23 September 1940. Just short of two years later, the collection of gold became enforced and systematic, as a consequence of the organisation of the Final Solution. Should the victim's family have requested the gold, the Reich's security service advised a reply as follows:

..... died in this camp, the corpse has been cremated on the....., which makes it impossible for us to send you back the dental gold.[3]

Hellinger was assigned to Ravensbrück, the camp for women, in 1943.[4] He was one of four camp dentists[3] along with Walter Sonntag.[5] The chief camp doctor was Karl Gebhardt.[6]

Dental provision at the camp was almost non-existent. Hellinger paid minimal attention to dental treatment and greater consideration of his role as an executive SS officer performing general duties alongside the other camp office members. His foremost duty was to remove and collect silver and gold teeth and fillings and tooth bridges to send on to Walther Funk, the President of the Reichsbank. After a medical officer had confirmed death and before any unauthorised removals could occur, Hellinger searched the mouths of the dead for gold.[2]

He was present at the executions of three British SOE agents: Lilian Rolfe, Denise Bloch and Violette Szabo.[5][7][8]

The Ravensbrück trial edit

The first Ravensbrück trial opened on 3 December 1946, six days before the Nazi doctors' trial in Nuremberg was opened by the United States.[9]

Sixteen members of the staff at Ravensbrück were tried by a mixed inter-allied court in the British zone between 5 December 1946 and 3 February 1947. All were found guilty, except one who died during the trial.[10] Eleven were sentenced to death.[9]

On arrival at the camp, Hellinger checked victims' teeth for gold that he could retrieve later.[5] In a pre-trial statement, Hellinger acknowledged that his duty was to remove gold teeth from dead bodies. This, he did either by himself or delegated to one of the prisoner assistants. In addition, he would extract gold teeth from "just-executed prisoners", having waited for them in the crematorium prior to the mass cremations.[11][12] He claimed he believed that the dead were legally executed.[13]

On 3 February 1947, a British military tribunal in Hamburg sentenced him to 15 years in prison. He was not of the opinion that he neglected his professional duties.[2]

Later life edit

The Federal Republic of Germany was founded in 1949, resulting in relaxed restrictions on the German courts. Further removal of restrictions occurred with the "Treaty of Transferral" between Germany and the United States, the UK and France on 5 May 1955.[14]

Hellinger was released from the British prison for war criminals in Werl on 20 May 1954 and re-established his dental practice with a special grant of 10,000 DM by the West German government as compensation for the time he spent in prison.[9][15][16][17] He practiced for many years after, and died in 1988. Six photographs of Hellinger are in the British National Archives.[18][19][20]

References edit

- ^ Hördler, Stefan (2015). Ordnung und Inferno: Das KZ-System im letzten Kriegsjahr (in German). Wallstein. p. 167. ISBN 9783835325593.

- ^ a b c d Liverpool, Lord Russell of (2013). The Scourge of the Swastika: A Short History of Nazi War Crimes. Frontline Books. ISBN 9781473877559.

- ^ a b Riaud, Xavier (January 2017). "Nazi Dental Gold: From Dead Bodies to a Swiss Bank". Dental Historian. 62 (1): 15–23. ISSN 0958-6687. PMID 29949310.(subscription required)

- ^ "The Polish Research Institute in Lund" (PDF). www.ub.lu.se. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Helm, Sarah (2015). If This Is A Woman: Inside Ravensbruck: Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-7481-1243-2.

- ^ Dörner, K, ed. (2001). The Nuremberg Medical Trial 1946/47:guide to the microfiche edition. Munich: K.G. Saur Verlag GmbH. p. 91. ISBN 978-3598321542.

- ^ Saidel, Rochelle G. (2004). The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. Terrace Books. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-299-19860-2.

- ^ Sugarman, Martin (1996). "Two Jewish heroines of the SOE". Jewish Historical Studies. 35: 309–328. JSTOR 29779992.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c Heberer, Patricia; Matthuus, Jurgen (2008). Atrocities on Trial: Historical Perspectives on the Politics of Prosecuting War Crimes. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-8032-1084-4.

- ^ "Ravenbruck accused all found guilty", The Advocate Newspaper, 4 February 1947.

- ^ Bazyler, Michael J.; Tuerkheimer, Frank M. (2015). Forgotten Trials of the Holocaust. NYU Press. pp. 141–144. ISBN 978-1-4798-8606-7.

- ^ Riaud, Xavier (December 2005). "Les dentistes allemands sous le lllè Reich" (PDF). Vesalius (in French). XI (2). Acta Internationalia Historiae Medicinae: 108.

- ^ "Saved Gold Teeth of Nazi Victims", Maryborough Chronicle, 25 January 1946, p. 1.

- ^ Priller, Christof (2013). Cook, Bernard A. (ed.). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 460–461. ISBN 978-0-815-31336-6.

- ^ Dornberg, John (1961). Schizophrenic Germany. Macmillan Publishers. p. 45.

- ^ Information Bulletin. 1961. p. 28.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Adler, Cyrus; Szold, Henrietta (1957). The American Jewish Year Book. American Jewish Committee. p. 282.

- ^ Drifte, Collette (2011). Women in the Second World War. Pen and Sword Books. p. 207. ISBN 9781844680962.

- ^ "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Image details – Martin Hellinger, Ravensbrueck War Crimes Trials | The National Archives Image library". images.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

Further reading edit

- "‘Enfer Des Femmes’: Britain and The Ravensbrück-Hamburg Trials", H. Stacey (2017) Masters thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University.

- Zum Selbstverständnis von Frauen im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück. PhD thesis

External links edit

- ostsachsen.projekt