Summary

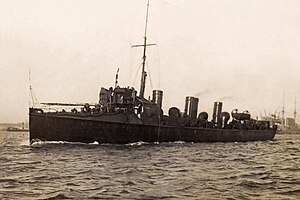

HMS Spiteful was a Spiteful-class torpedo boat destroyer built at Jarrow, England, by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company for the Royal Navy and launched in 1899. Specified to be able to steam at 30 knots, she spent her entire career serving in the seas around the British Isles.

HMS Spiteful

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Spiteful |

| Builder | Palmers, Jarrow |

| Cost | £50,977 |

| Laid down | 12 January 1898 |

| Launched | 11 January 1899 |

| Completed | February 1900 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sold for scrap 14 September 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Spiteful-class torpedo boat destroyer, classified as B-class in 1913 |

| Displacement | 400 tons (406.4 tonnes) |

| Length | 220 ft (67.1 m) overall |

| Beam | 20 ft 9 in (6.3 m) |

| Draught | 9 ft 1 in (2.77 m) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) |

| Range | 4,000 NM (at 13.05 knots) |

| Complement | 63 |

| Armament |

|

In 1904 Spiteful's boilers were modified to burn fuel oil. Tests were conducted by the Royal Navy in that year, comparing her performance using oil directly with that of a similar ship using coal, in which it was proved that burning oil offered significant advantages. This led to the adoption of oil as the source of power for all warships built for the Royal Navy from 1912. In 1913 Spiteful was classified as a B-class destroyer. She was sold and scrapped in 1920.

Design and construction edit

HMS Spiteful was one of about 60 torpedo boat destroyers built for use by the Royal Navy between 1893 and 1900 to the specifications of the Admiralty; she was also the 50th ship built for the Admiralty by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company, and the 12th torpedo boat destroyer built by them.[1][2][3] By the time of her construction, Palmers had come to be regarded as one of the "more successful builders [of this type of ship]".[4] She was laid down on 12 January 1898 at Palmers' Jarrow shipyard and launched on 11 January 1899, at a cost of £50,977.[5] She arrived at Portsmouth for completion on 31 August 1899, and this was achieved in February 1900.[6][Fn 1]

Her design was a development of that for Palmers' Star-class torpedo boat destroyers, which had been completed between 1897 and 1899, although most changes were minor.[8] For example, whereas the Star-class ships had three funnels, of which the middle one was more substantial, Spiteful had four, of which the central two were grouped closely together.[9][Fn 2] Spiteful's length overall was 220 feet (67.1 metres), her beam was 20 feet 9 inches (6.3 m) and her draught was 9 ft 1 in (2.77 m).[11] Her light displacement was 400 tons (406.4 tonnes).[9]

In common with similar Royal Navy ships of the time, Spiteful's forecastle was of the "turtle-back" type with a rounded top: this design was intended to keep the forecastle clear of sea water, but in practice had the adverse effect of digging a ship's bow into the sea when it was rough, thereby making ships lose speed, besides making them "wet and uncomfortable".[12][13][Fn 3] Wetness was mitigated by screening across the rear of the forecastle and around the forward gun position, a raised platform below which was the enclosed conning tower.[17][18][Fn 4] A foremast stood behind the conning position and was fitted with a derrick.[21][Fn 5] She was armed with a QF 12-pounder gun located in the forward gun position; five QF 6-pounder guns, four of which were arranged along her sides and one located centrally on a raised platform towards her stern, as a rear gun; and a pair of 18-inch (460-millimetre) torpedo tubes on a horizontally rotating mount located on deck towards the stern, ahead of the rear gun.[23][21][24][Fn 6] The crew numbered 63 officers and men, for whom the accommodation on this type of ship was "very cramped; usually the captain had a small cabin but ... other officers lived in the wardroom."[26][Fn 7] The remainder of the crew slept in hammocks.[27][Fn 8] As ordered Spiteful probably carried four boats, comprising a gig, a dinghy and two lifeboats of the Berthon type.[22][Fn 9]

Admiralty specifications in force at the time of her construction required that she should be able to steam at 30 knots, and from this she was one of a group of torpedo boat destroyers known informally as "30-knotters".[28] Spiteful's propulsion was through two propellers, each driven by one of two triple expansion steam engines that were powered by four coal-fired Reed water tube boilers operated at 250 pounds per square inch (1,724 kilopascals) and could produce 6,300 hp (4,698 kW) indicated horsepower (IHP).[29][Fn 10] In ships of her type the boilers were installed in a line fore-and-aft and in pairs, so that in each pair the furnace doors faced each other: thus one group of stokers could tend two boilers simultaneously, and only two boiler rooms, also known as stokeholds, were required.[27][Fn 11] In sea trials it was found that, when run at 29.9 knots, she consumed 2.3 pounds (1 kilogram) of coal per IHP per hour, which was considered low, and a speed of 30.371 knots was "easily maintained".[33][Fn 12] At 13.05 knots it was found that her capacity of about 91 tons (92.5 tonnes) of coal, consumed at a rate of 1.5 pounds (0.7 kg) per IHP per hour, gave her a steaming range of about 4,000 nautical miles.[34][33][Fn 13]

Torpedo boat destroyers of the 30-knotter specification featured watertight bulkheads that enabled them to remain afloat despite damage to their hulls, which were thin and lightly built for speed.[37][38] Conversely the thinness of their hulls meant that they were easily damaged by stormy seas and careless handling.[39][37] Those that were based in British ports, as Spiteful was, were originally painted black overall, but they would have been painted grey by about 1916, from which point they would also have had their pendant numbers painted on their bows.[40][41][Fn 14] Spiteful and her sister ship Peterel, also built by Palmers and launched later the same year, formed the Spiteful class.[23][43][44][Fn 15]

At the time of their construction a specification of 30 knots made for a fast warship, but:

[t]here seems to have been little rational discussion of why high speed was necessary ... Speed was seen as a good thing in itself. It became a subject for international competition. The specialist torpedo boat firms all competed for the fastest speed on water. ... [However] very few of the "30-knotters" could make more than about 26 knots, if that, in service and this was only in calm conditions.

Otherwise,

[t]he best advertisement for [the 30-knotters] lay in the fact that they were worked very hard during [the First World War] and, though most of them were twenty years old by 1919, they remained efficient. This [also] speaks well for their builders ...

— T.D. Manning, The British Destroyer, 1961[37]

These builders were all private British enterprises that had previously specialised in building torpedo boats, and, regarding their designs for 30-knotters, it was specified that they should be given "[a]s free a hand as possible".[49] In 1996 David Lyon, curator of ships’ plans at the National Maritime Museum, wrote that Palmers' torpedo boat destroyers in particular "eventually would, by common consent, be considered the best all-rounders of all".[50][51]

Service history edit

Spiteful always served within the vicinity of the British Isles.[9][23][Fn 17] From 10 July to 3 August 1900 she was engaged in a naval exercise conducted in the Irish Sea, during which she was deemed to have been put out of action.[53][Fn 18] From 11 January 1901 to 24 February 1902 at the latest she was captained by Commander Douglas Nicholson, who later became a vice admiral.[54][55] In February 1901 she ran aground near the Isle of Wight, damaging her propellers, and was taken to Portsmouth dockyard for overhaul.[56] On 23 October the same year, while off the north-eastern coast of England, she had a collision with her sister ship Peterel, in which her stem was twisted and her bow "partly torn away".[57][Fn 19] On 4 April 1905, while steaming at 22 knots near Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight, she collided with the barge Preciosa, which was carrying bags of cement.[59] Damage to Spiteful's bow and forward superstructure was severe, but that damage was not greater was attributed to her "light build"; one of Spiteful's crew was slightly injured, but the barge sank and two of her crew drowned.[59][60][Fn 20] On 5 August 1907, while she was raising steam at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, fuel oil was released under pressure from a disconnected burner, causing flames to fill the rear boiler room: two members of the crew were killed and two were injured.[62][63][64][Fn 21] The magazines were flooded to protect them from the fire and, although it caused no structural damage, Spiteful was later towed to Portsmouth for inspection.[65] She was part of the Portsmouth flotilla of the Home Fleet at the time.[65] The event prompted the Admiralty to issue new instructions on the handling of fuel oil in its ships, particularly after overhaul.[64]

In 1913 Spiteful was classified as a B-class destroyer.[66][23] From June 1914, one month before the outbreak of the First World War, the Royal Navy's Navy List records that she was based at Portsmouth as a tender for HMS Vernon, the Admiralty's torpedo training school: her "Chief Artificer Engineer" was based there, rather than on board.[67][Fn 22] From August 1914 she was listed as still based at Portsmouth, but no longer as a tender for Vernon, although her chief artificer engineer remained there.[69] From June 1915 she was listed as part of the Portsmouth Local Defence Flotilla.[70] On 6 September 1916 she sighted a German submarine off Cape Barfleur, in the English Channel, forcing it to dive.[71] On 18 January 1917 Spiteful was despatched from Portsmouth with three other destroyers to go to the aid of HMS Ferret, another destroyer that had been disabled by an enemy torpedo while hunting German submarines in mid-Channel south-east of the Isle of Wight; Ferret was recovered to Portsmouth.[72][Fn 23] On 27 August 1917 Spiteful was reported entering Lough Swilly, in north-western Ireland, along with destroyers Fawn, Wolf and Violet.[73] From May to December 1918, by which time the war had ended, Spiteful was again listed as part of the Portsmouth Local Defence Flotilla, but also as a tender for "HMS Victory", as Portsmouth Naval Barracks were named at the time.[74][75][76] From January to April 1919 she was listed only as based at Portsmouth, but in May that year she was listed as being based there without an officer in command.[77][78][79][Fn 24] She did not appear in the Navy List again until January 1920, when she was listed as "To Be Sold".[82] This occurred on 14 September 1920, and she was broken up at Hayes' yard, Porthcawl.[9][42][43]

Fuel oil edit

Spiteful was instrumental in the Royal Navy's adoption of fuel oil as a source of power in place of coal. Her boilers were modified to burn only fuel oil as part of ongoing experiments and, on 7–8 December 1904, "vitally important" comparative trials were carried out near the Isle of Wight with Spiteful's sister ship Peterel burning coal, in which Spiteful performed significantly better.[83][84][85][Fn 25] Problems with the production of smoke were surmounted so that using oil produced no more smoke than coal, and it was found that the ship's crew could be reduced, since fewer were required in the boiler rooms.[87][Fn 26] Whereas Peterel required six stokers during the trials, Spiteful required only three boiler-room crew; while Peterel's crew had to dispose of 1.5 tons (1.52 tonnes) of ash and clinker, Spiteful produced no such waste.[83][Fn 27] Further, while Peterel took 1.5 hours to prepare for steaming, Spiteful took 10 minutes.[83] In June 1906, the journal Scientific American journal reported that Spiteful was being used by the Admiralty to train engine-room crews in the operation of oil-burning equipment.[93]

That a navy's reliance on coal entailed problems of logistics and strategy was understood well before the trials took place:

We have, at sea, command of very high speeds, but we pay a ruinous price for the luxury. [At a chosen] speed we can steam long distances, but if we are hustled, we draw heavily on [that ability]. A fleet with many coal bases can … hustle another into inability to [choose its destination] – we can … head off [a] fleet from astern. This limitation of distance capacity, [and] invisible control over the destination of an enemy, … gives a new meaning to the word "blockade" … That coal can be carried with a fleet and distributed under certain conditions is obvious, [but] to place reliance on [it] is out of the question.

Thus Bacon argued that a navy reliant on coal must have a "coal strategy".[94] Using fuel oil instead removed this strategic limitation and offered significant advantages:

[Oil] had double the thermal content of coal so that boilers could be smaller and ships could travel twice as far. Greater speed was possible and oil burned with less smoke so the fleet would not reveal its presence as quickly. Oil could be stored in tanks anywhere, allowing more efficient design of ships, and it could be transferred through pipes without reliance on stokers, reducing manning. Refueling [sic] at sea was feasible, which provided greater flexibility.

— E.J. Dahl, "Naval innovation: From coal to oil", 2000[95]

In addition, construction costs for an oil-powered warship were lower by an average of 12.4% – a destroyer would be cheaper by a third – and carrying oil instead of coal meant that a warship's armaments and armour could be heavier.[96][97]

Although the trials of 1904 proved the superiority of fuel oil over coal in powering warships, they did not lead to the immediate abandonment of coal as a source of power by the Royal Navy. While Britain's internal supply of coal was plentiful, it had no such supply of oil, either domestically or within its empire.[98] William Palmer, who was First Lord of the Admiralty in 1904, regarded a change to oil as "impossible", for reasons of availability.[99][Fn 29] This took time to overcome, but it was achieved through foreign policy and government activity in the oil market, beginning with the Royal Commission on Fuel and Engines of 1912. This was established by Winston Churchill, who was First Lord of the Admiralty at the time.[100] The Navy committed itself to change in the same year, when all of the ships that it set out to procure were designed to use fuel oil.[101][Fn 30]

References edit

Footnotes edit

- ^ Spiteful's date of commissioning has not been found. The earliest ship's log for Spiteful, held at The National Archives under reference ADM 53/26547, was begun on 24 April 1900.[7]

- ^ A correspondent to The Engineer described Spiteful as having one central funnel that "look[ed] like two bound together".[10]

- ^ The performance of the turtle-back forecastle in heavy weather is shown in a photograph published in 1899 of HMS Banshee.[14][15] During a heavier storm in the Mediterranean Sea in 1911, Banshee "was constantly swept fore and aft by the seas."[16]

- ^ Spiteful's plans are at the National Maritime Museum,[19] and include one "as fitted" of 7 January 1901 corrected to 28 September 1905.[20] There the forward gun position is labelled "Bridge". The same plan shows that Spiteful had three ship's wheels: one on the bridge behind the forward gun, one below in the conning tower and one on deck at the stern.

- ^ A rigging plan for a similar ship, HMS Albatross of 1898, shows her derrick being used to launch a Berthon boat from her deck.[22]

- ^ On the plan for Spiteful corrected to 28 September 1905, one QF 6-pounder gun is mounted on each side of the deck in a position between the QF 12-pounder forward gun and the foremast, a third is mounted on the port side slightly forward of the central pair of funnels, and a fourth is mounted on the starboard side slightly aft of the after funnel. The rear QF 6-pounder gun is on a raised mount and is provided with a circular firing platform about 2 ft (0.61 m) above the level of the deck, accessed by two short ladders. The plan shows that this gun formerly had a simple, flat shield, which has been removed. On the same plan, a single torpedo tube is mounted in the rear position and a second one is mounted forward of the rear funnel.[20] This arrangement is similar to that adopted for earlier torpedo boat destroyers, for example HMS Haughty, launched in 1895.[25]

- ^ Sources do not specify the number of Spiteful's crew directly: Manning 1979, p. 45, gives details of five torpedo boat destroyers built by Palmers between 1898 and 1901, including Spiteful, as a group, and says that they all had a crew of 63. That these ships' details varied can be seen by comparison with Lyon 2005, esp. p. 80. However the number of 63 for Spiteful's crew is given further indirect support in Lyon 2005, p. 32, where it is reported that the number of crew proposed for HMS Cobra in 1901 was "twenty-one men more than for a 30-knotter giving a total complement of eighty-four".

- ^ On the plan of 1901, corrected to 28 September 1905, the cabin for Spiteful's captain is at the stern, forward only of a storeroom for provisions. The wardroom is forward of the cabin and separated from it by a lavatory, for washing only, and pantry: a small toilet compartment is in the rear, port corner of the wardroom, which also contains three "bedplaces" and wardrobes and a secretaire. Immediately forward of the latter is a mess for engine room artificers on the port side and chief petty officers on the starboard. A mess for other ranks is in the forecastle, with lockers for stowing hammocks.[20]

- ^ On the plan of 1901, corrected to 28 September 1905, Spiteful is shown as having two Berthon boats 20 ft (6.1 m) long, one each side of the forward funnel, a whaler 25 ft (7.6 m) long carried on davits on the port side and astern of the rear funnel, and a dinghy 13 ft 6 in (4.1 m) long carried similarly but on the starboard side. The plan also states that 56 lifebelts are carried.[20]

- ^ Since the propellers projected significantly beyond either side of Spiteful's stern, as they did in other ships of her type, propeller guards were fitted at the height of the rubbing strake:[20] compare ships' plans at Lyon 2005, e.g. p. 22.[30] A triple expansion engine built by Palmers and of the type used in Spiteful is illustrated at Dillon 1900, p. 33.[31]

- ^ The arrangement of the boilers was reflected in that of the funnels:[20] compare the plan for HMS Arab and its caption at Lyon 2005, pp. 28–29. A stoker could be a fireman feeding a boiler with coal or a trimmer extracting coal from a bunker and delivering it to the fireman.[32] In 1901, in connection with HMS Cobra, it was assumed that a fireman would move about 18 cwt (914 kg) of coal per hour, and a trimmer about 30 cwt (1.52 t).[32]

- ^ In this trial "it was desired to keep the speed as little in excess of 30 knots as possible."[33]

- ^ This is not an unrealistic figure: the radius of action for a similar ship, HMS Ardent of 1894, was given as 2,750 nautical miles at 13 knots.[35] However, while Brassey 1902, p. 275, reported both Spiteful and Peterel's coal capacity to be 91 tons, the US Office of Naval Intelligence reported Spiteful's to be "about 116 tons": presumably these are US "short tons", giving an equivalent of 103.6 tons (105.2 tonnes).[33] Spiteful's Commander Douglas Nicholson wrote on 7 August 1901 that, whereas the turbine-powered HMS Viper had consumed on average 6 tons (6.1 tonnes) of coal per hour steaming at an average of 22 knots from Portland harbour to the Lizard and back, with a "slight sweep towards the French coast [...,] Spiteful could have done the same thing at almost the same speed with an average of 2 tons an hour."[36] However Lyon 2005, p. 31, considers this estimate of Spiteful's performance to be exaggerated. The nature of the information reported for the sea trials may be compared with the conditions of tendering for 30-knotters issued by the Admiralty in March 1895: see Lyon 2005, p. 23. A port-side-view line drawing of Spiteful as she was in 1912, useful for interpreting the arrangement of many of the ship's external features, is at Lyon 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Spiteful's pendant number until 1915 was P 73, after which it was D 91 until 1918, when it was changed again to D 76.[42]

- ^ Classification of torpedo boat destroyers (TBDs) before 1913 appears to have been ad hoc: "[t]here were at least occasions when some at least of the TBDs were referred to in classes designated by a ship's name. W. H. White referred in ... 1893 to the 'Boxer Class' when he could be referring either to Thornycroft's 27-knotters or to the first order for 27-knotters, or to all the 27-knotters. To confuse matters, ... at least some of the 27-knotters were referred to as the Ardent class (an exact sister of Boxer!) ... For the 30-knotters there is a general reference to all the first TBDs ... as the Desperate class. However there is also a reference to separate ... classes."[45]

- ^ The reason for the emphasis on speed and lightness was further illustrated somewhat later when, "[i]n 1912, [Admiral] Fisher wrote to [Winston] Churchill, 'What you do want is the super-swift – all [fuelled by] oil – and don't fiddle about armour; it really is so very silly! There is only one defence and that is speed!'"[47] But in sea trials for these ships "[s]pecial courses were used, which later research would show were exactly the right depth to produce an enhanced and unrealistic top speed. Trials were run in calm water, with specially trained crews of stokers and, literally, hand-picked coal. Very often ... the strain on the machinery [was] so great that there was permanent damage."[38] And Director of Naval Construction W.H. White had previously noted in 1897 that "the limit of speed attainable is very commonly fixed by the condition of the sea rather than by the power available in vessels."[48]

- ^ In 1891 John Fisher, who was then Third Sea Lord, wrote that the Royal Navy's "real line of defence [lay] on the French side of the [English] Channel".[52]

- ^ The naval exercise of 1900 is described and discussed in detail at Thursfield 1901.

- ^ The US Office of Naval Intelligence reported that Spiteful collided with a ship named "Petrel" while on service with the "reserve fleet".[57] While there was no Royal Navy ship named Petrel, this is clearly an error for "Peterel": compare Office of Naval Intelligence 1900, p. 42. The Reserve Fleet consisted of ships not in active service. Nicholson was similarly unfortunate in his next command, of HMS Dove.[58]

- ^ The collision occurred while Spiteful was undergoing trials in the use of fuel oil. The drowned men were the barge's skipper Thomas Daniels and her cook James Balderson.[59] At the time of the collision the ship's captain, Lieutenant Commander Abbott, was below deck having left Sub-Lieutenant G. T. Saundby in charge. After a court martial Saundby was "deprived of six months' seniority and dismissed [from] his ship."[61]

- ^ The two crew members killed were petty officer stoker George Stubbs, of Portsmouth, and first class stoker Alfred Dunn, of Bristol; first class stoker Ernest Edwin Westbrook was severely injured, but later reported to be recovering, and engine room artificer William Frederick Buckland was slightly injured. The ship had been inspected by King Edward VII on the preceding Saturday.[65]

- ^ The Royal Navy rank of Chief Artificer Engineer was created by an Admiralty Order in Council of 28 March 1903 as a rank senior to that of Artificer Engineer and of the same seniority as those of Chief Gunners, Chief Boatswains and Chief Carpenters.[68] At the time of its creation, the rank of Chief Artificer Engineer was limited to 44 personnel for one year, after which they were to number no more than a third of the combined total of themselves and Artificer Engineers. Engineering ranks in the Royal Navy in 1914 are discussed in detail in Anon. 1914, pp. 583–589, but the rank of Chief Artificer Engineer does not appear explicitly.

- ^ Besides Spiteful, the destroyers despatched from Portsmouth were HMS Druid, HMS Hind and HMS Sandfly: Ferret was also based at Portsmouth, and was towed there by Druid.[72]

- ^ A supplement of January 1919 lists her among vessels at their home port of Portsmouth "temporarily".[80] Later in 1919 similar ships were listed as paid off, for example in the Navy List for July, but Spiteful was not among them.[81]

- ^ Spiteful and other 30-knotter torpedo boat destroyers ordered by the Admiralty at about the same time already incorporated "[a]rrangements ... for burning oil only or oil and coal together."[86]

- ^ Lower production of smoke made a ship less visible to an enemy.[88] "[F]laming at the funnels [was] a constant menace" in revealing a ship's position at night, but the Admiralty aimed to prevent this in its torpedo boat destroyers through its specifications for them from November 1898.[89]

- ^ Marine "ash ejectors" were developed and adopted in the early 20th century, allowing ash and clinker to be ejected directly from a boiler room, but this waste was fed into them manually.[90][91] For example, See's ash ejector, which was patented at the United States Patent Office in 1901, required "[t]he ashes to be ejected [to be] thrown in any suitable way into [a] hopper".[92] If Spiteful had been fitted with ash ejection systems at any time, they are not shown on the plan "as fitted" of 7 January 1901, corrected to 28 September 1905, by which time she was oil-fired.[20]

- ^ "Moving [coal] from shore to ship, and aboard ship, was dirty and strenuous work that required extensive man-power. As Churchill noted, 'the ordeal of coaling ship exhausted the whole ship's company. In wartime it robbed them of their brief period of rest; it subjected everyone to extreme discomfort.' It was virtually impossible to refuel at sea, meaning that a quarter of the fleet might be forced to put into harbor [sic] coaling at any one time. Providing the fleet with coal was the greatest logistical headache of the age."[95]

- ^ The oil used in Spiteful's trials was from Texas, in the United States.[83]

- ^ Some coal-burning ships continued to be built for the Navy: Revenge-class battleships built in 1913 were so designed, because of continuing uncertainty over supplies of oil and their cost implications, but their design was changed to burn oil during construction, after the outbreak of the First World War.[102]

Notes edit

- ^ Cocker 1981, p. 11.

- ^ Anon. 1899a, p. 475.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 77–80.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 80; Gardiner 1979, p. 96; "Destroyers before 1900". battleships-cruisers.co.uk. n.d. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016; Anon. 1899a, p. 475; Hurd 1914, p. 98.

- ^ "Naval and military intelligence". The Morning Post. 1 September 1899. p. 5. Retrieved 23 February 2018.; Lyon 2005, p. 80.

- ^ "Spiteful". The National Archives. n.d. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 78–80.

- ^ a b c d Lyon 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Anon. 1899b, p. 430.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 78 & 80.

- ^ Cocker 1981, pp. 14–18.

- ^ Manning 1979, pp. 33, 39.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 110 (caption).

- ^ "Torpedo boat destroyer HMS Banshee in a rough sea, 1899". Wikimedia Commons. 1899. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Manning 1979, p. 24.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Plan of the ship HMS Spiteful (1899)". Royal Museums Greenwich. n.d. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ a b Cocker 1981, p. 17.

- ^ a b Lyon 2005, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d Manning 1979, p. 45.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Manning 1979, pp. 34, 45.

- ^ a b Lyon 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Manning 1979, pp. 39–46.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 78 & 80; Office of Naval Intelligence 1900, p. 42; Anon. 1899c, p. 514; Office of Naval Intelligence 1900, p. 42.

- ^ "Palmers Reed boiler". WikiMedia Commons. 1900. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Palmers triple expansion engine". WikiMedia Commons. 1900. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ a b Lyon 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Brassey 1902, p. 275.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Manning 1979, p. 39.

- ^ a b Lyon 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 16, 112–113.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Manning 1979, p. 34.

- ^ a b "'Arrowsmith' List: Royal Navy WWI Destroyer Pendant Numbers". www.gwpda.org. 1997. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ a b Gardiner 1979, p. 96.

- ^ "Destroyers before 1900". battleships-cruisers.co.uk. n.d. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Dahl 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 14, 23.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Grove, E. (August 2000). "Obituary: David Lyon". The Society for Nautical Research. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 14.

- ^ "Naval and military intelligence". The Times. 1 January 1901. p. 12. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Seven to Admiral Sir D.R.L. Nicholson, Royal Navy". Bonhams. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Naval and military intelligence". The Times. 5 March 1901. p. 8. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Naval and military intelligence". The Times. 11 June 1902. p. 13. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "HMS Spiteful in collision". The Times. 5 April 1905. p. 8. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Anon. 1905, p. 555.

- ^ "The destroyer Spiteful leaps across the deck of the ketch Preciosa: A thrilling moment". The Penny Illustrated Paper and Illustrated Times. 22 April 1905. p. 247. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Anon. 1907a, pp. 1097–1098.

- ^ Anon. 1907b, p. 55.

- ^ a b Anon. 1908a, p. 368.

- ^ a b c "Naval and military intelligence". The Times. 7 August 1907. p. 8. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Anon. 1913, p. 450.

- ^ Admiralty 1914a, p. 376.

- ^ Admiralty 1908, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Admiralty 1914b, p. 381a.

- ^ Admiralty 1915, p. 17.

- ^ Newbolt 1928, p. 335.

- ^ a b Admiralty 1933, p. 150.

- ^ Fisher, J., ed. (2016). "HMS Virginian – December 1914 to November 1918, Northern Patrol (10th Cruiser Squadron), North Atlantic convoys". Royal Navy Log Books of the World War 1 Era. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Admiralty 1918a, p. 28.

- ^ Admiralty 1918b, p. 16.

- ^ "Main Bases, Training Schools and RN Air Stations". www.mariners-l.co.uk. 2002. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Admiralty 1919a, p. 910.

- ^ Admiralty 1919b, p. 910.

- ^ Admiralty 1919c, p. 910.

- ^ Admiralty 1919d, p. 20.

- ^ Admiralty 1919e, p. 20.

- ^ Admiralty 1920, p. 1105f.

- ^ a b c d Lyon 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Brassey 1905, p. 449.

- ^ Bertin 1906, p. 167.

- ^ Lyon 2005, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Anon. 1904b, p. 27.

- ^ McCain, J. (20 March 2008). "John McCain: Extraordinary foresight made Winston Churchill great". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Lyon 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Anon. 1914, pp. 1342–1344.

- ^ Sothern 1917, pp. 148–149.

- ^ US patent 674021, See, H., "Ash-ejector", published 1901-05-14, issued 1901-05-14.

- ^ Anon. 1906, p. 491.

- ^ a b Bacon 1901, p. 246.

- ^ a b Dahl 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Winegard 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Siegel 2002, p. 180.

- ^ Dahl 2001, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Siegel 2002, pp. 178–184.

- ^ Siegel 2002, p. 181.

- ^ Brown2003, pp. 105–106.

Bibliography edit

- Admiralty (1908), The Orders in Council for the Regulation of the Naval Service, vol. 9, HMSO

- Admiralty (1914a), The Navy List, for July, 1914, Corrected to the 18th June, 1914, HMSO

- Admiralty (1914b), The Navy List, for September, 1914, Corrected to the 18th August, 1914, HMSO

- Admiralty (1915), Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officers' Commands, &c., HMSO

- Admiralty (1918a), Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officers' Commands, &c., HMSO

- Admiralty (1918b), Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officers' Commands, &c., HMSO

- Admiralty (1919a), The Navy List, for February 1919, Corrected to the 18th January, 1919, HMSO

- Admiralty (1919b), The Navy List, for May 1919, Corrected to the 18th April, 1919, HMSO

- Admiralty (1919c), The Navy List, for June 1919, Corrected to the 18th May, 1919, HMSO

- Admiralty (1919d), Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officers' Commands, &c., HMSO

- Admiralty (1919e), The Navy List, for July 1919, Corrected to the 18th June, 1919, HMSO

- Admiralty (1920), The Navy List, for January, 1920, Corrected to the 18th December, 1919, HMSO

- Admiralty (1933), Naval Staff Monographs (Historical) Volume XVIII: Home Waters Part VIII (PDF), Naval Staff, OCLC 561358029, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2016

- Anon. (1 February 1899a), "Launches and Trial Trips", The Marine Engineer, 20: 474–6, OCLC 10460390

- Anon. (27 October 1899b), "Dockyard notes" (PDF), The Engineer: 430, OCLC 5743177, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017, retrieved 19 February 2017

- Anon. (24 November 1899c), "Trials of a Jarrow destroyer" (PDF), The Engineer: 514, OCLC 5743177, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017, retrieved 19 February 2017

- Anon. (1904a), "Notes from the South-West", Engineering, 78, OCLC 7540352

- Anon. (1904b), "The British Admiralty ...", Scientific American, 91 (2), ISSN 0036-8733

- Anon. (1905), "Spiteful – Accident to", Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, 17: 555, OCLC 637558568

- Anon. (1906), "The British Naval Programme for 1906", Scientific American, 94 (24), ISSN 0036-8733

- Anon. (1907a), "Accidents to British torpedo-boat destroyers", Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, 19: 1097–8, OCLC 637558568

- Anon. (1907b), "Portsmouth dockyard", The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect, 30 (September 1907): 55, OCLC 31366734

- Anon. (1908a), "Oil fuel regulation", United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 34 (1): 368, OCLC 42648595

- Anon. (1908b), "Machinery and boilers", United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 34 (1): 712–3, OCLC 42648595

- Anon. (24 October 1913), "Dockyard notes" (PDF), The Engineer: 450, OCLC 5743177, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017, retrieved 19 February 2017

- Anon. (1914), "Engineers and engineering in the Royal Navy", Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, 26: 583–9

- Bacon, R.H.S. (1901), "Some notes on naval strategy", in Leyland, J. (ed.), The Naval Annual 1901, pp. 233–52, OCLC 496786828

- Bertin, L.E. (1906), Marine Boilers: Their Construction and Working Dealing More Especially with Tubulous Boilers, trans. & ed. L.S. Robertson (2nd ed.), van Nostrand, OCLC 752935582

- Brassey, T.A., ed. (1902), The Naval Annual 1902, OCLC 496786828

- Brassey, T.A., ed. (1905), The Naval Annual 1905, Griffin, OCLC 496786828

- Brown, W.M. (2003), The Royal Navy's Fuel Supplies, 1898 – 1939: The Transition from Coal to Oil (PDF), King's College London PhD thesis, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 29 November 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cocker, M. (1981), Destroyers of the Royal Navy 1893–1981, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-1075-7

- Dahl, E.J. (2001), "Naval innovation: From coal to oil" (PDF), Joint Force Quarterly (Winter 2000–01): 50–6, archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2016, retrieved 28 November 2016

- Dillon, M. (1900), Some Account of the Works of Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company, Franklin, OCLC 920223009

- Gardiner, R., ed. (1979), Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905, Conway Maritime, ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5

- Hurd, A. (1914), The Fleets at War, Hodder and Stoughton, OCLC 770497

- Lyon, D. (2005) [1996], The First Destroyers, Mercury, ISBN 1-84560-010-X

- Manning, T.D (1979) [1961], The British Destroyer, Godfrey Cave Associates, ISBN 0-906223-13-X, OCLC 6470051

- Newbolt, H. (1928), History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, vol. 4, Longmans, Green, OCLC 832233425

- Office of Naval Intelligence (1900), Notes on Naval Progress, July 1900, General Information Series: Information from Abroad, vol. 19, United States Government Printing Office, OCLC 19682402

- Office of Naval Intelligence (1901), Notes on Naval Progress, July 1901, General Information Series: Information from Abroad, vol. 20, United States Government Printing Office, OCLC 8182574

- Office of Naval Intelligence (1902), Notes on Naval Progress, July 1902, General Information Series: Information from Abroad, vol. 21, United States Government Printing Office, OCLC 19682598

- Siegel, J. (2002), Endgame: Britain, Russia, and the Final Struggle for Central Asia, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-371-2

- Sothern, J.W.M. (1917), "Verbal" Notes and Sketches for Marine Engineers: A Manual of Marine Engineering Practice (9th ed.), Munro, OCLC 807203242

- Thursfield, J.R. (1901), "British Naval Manoeuvres", in Leyland, J. (ed.), The Naval Annual 1901, pp. 90–118, OCLC 496786828

- Winegard, T.C. (2016), The First Oil War, Toronto University, ISBN 978-1-4875-0073-3