Summary

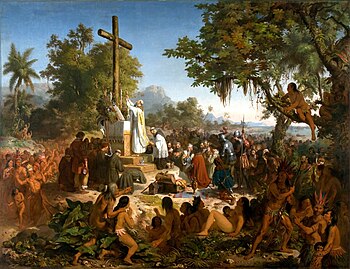

The First Mass in Brazil (Portuguese: Primeira Missa no Brasil) is an oil painting of the historical genre by Brazilian painter Victor Meirelles. It is considered Meirelles' first major work. The painting was created between 1859 and 1861,[1] in Paris, during the period when the artist lived in Europe on a scholarship granted by the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. Covering an area of 9 m2, The First Mass in Brazil was inspired by the letter written by Pero Vaz de Caminha to the king of Portugal describing the first mass held in the country.[2]

| The First Mass in Brazil | |

|---|---|

| Primeira Missa no Brasil | |

| |

| Artist | Victor Meirelles |

| Year | 1859-1861 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Movement | Academicism |

| Dimensions | 270 cm × 357 cm (110 in × 141 in) |

| Location | Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro |

Meirelles' painting style is influenced by European aesthetic standards that sought to create heroic figures and exalt nature.[3] The aesthetic nature of the work is related to the moment of affirmation of the Brazilian State and the construction of the country's identity, also in the visual arts.[4]

The painting became one of the most popular and recognized artworks in the country[1] and, exhibited at the Official Salon of Paris in 1861, it was the first Brazilian artwork to participate in a relevant international exhibition. The work also granted Meirelles the title of Imperial Knight of the Order of the Rose and the position of honorary professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.[5]

Description edit

The large size of the painting, 2.70 by 3.57 meters,[6] is a common characteristic of historical paintings, the genre to which The First Mass in Brazil belongs.[7] The painting represents the first mass celebrated in Brazil based on the travel accounts of Pero Vaz de Caminha. In it, the moment is depicted in a circular arrangement around the main figure, friar Henrique de Coimbra, who also occupies the physical center of the painting while lifting the chalice. The groups represented by Meirelles, local amerindians and the Portuguese, are differentiated both by their physical characteristics and their attitude towards the mass. While the Portuguese kneel and maintain a serious posture before the altar, the amerindians are depicted among the trees and the ground, engaging in conversation and showing signs of strangeness caused by the event.[5] Despite the differences between the groups, they all watch the mass harmoniously and demonstrate respect and concentration during the ceremony.[1][2]

The central nucleus of the work, where the altar supporting the wooden cross is located, was inspired by the work of Horace Vernet, La première messe en Kabylie. The French artist became one of Meirelles' main references for the construction of the work, but the Brazilian painter distanced himself from Vernet by choosing to portray the scene with more lightness.[2] The main illumination also falls on the central nucleus, leaving the foreground, composed of the Indians, in a shadowed area. The landscape, which mainly composes the background of the painting, also reaches the foreground, where it becomes part of the scene involving the figures participating in the ritual.[5] The depicted nature belongs to the Brazilian Northeast region, and the Indians, despite displaying body paintings, are idealized representations without indications of a specific ethnicity.[2]

Context edit

The First Mass in Brazil was executed at a time when the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute, founded in 1838, alongside the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, sought to establish founding myths of the country's history. Based on Jesuit experiences, the concept of the nation that they sought to narrate aligned with the idea of a civilizing process as a means to ensure State control over indigenous populations. Meirelles was influenced by this system of creating visual references, especially in historical painting, through research of historical documents and the construction of heroic characters and background elements that exalt nature.[3]

The work was created during the period when Victor Meirelles lived in Europe thanks to a scholarship granted to improve his academic knowledge.[8] Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, then director of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, suggested the theme of the founding myth of Brazil with the intention of obtaining government support to promote the development of Fine Arts in the country.[1] The painter used the Letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha as a major reference, a document that describes the Europeans' first impressions of Brazil and the first mass held in the country.[8]

Analysis edit

The First Mass in Brazil is considered by some theorists to be the precursor of historical paintings in Brazil.[7] One characteristic of this genre is verisimilitude, that is, the pretense of reproducing a scene exactly as it happened.[5] In addition to the characteristics of historical paintings, Meirelles was influenced by the painting La première messe en Kabylie by Horace Vernet. The thorough analysis of the French painting, presented at the Salon de Paris in 1855, was motivated by being a reference in which the artist was an eyewitness to the scene: Vernet attended the mass that celebrated the French colonization in North Africa. The French work carried a legitimacy in the parameters of historical painting that inspired the Brazilian painter.[9]

The painting, considered Meirelles' first major work, became one of the most popular artworks in Brazil[1] and is frequently featured in history textbooks.[10] The significance of The First Mass in Brazil was recognized the year after its completion when, in 1861, it was exhibited at the Official Salon of Paris. It was the first time a Brazilian artist participated in an internationally renowned exhibition, marking not only Meirelles' career but also that of the Imperial Academy.[citation needed]

The work and national identity edit

Together with other works by Pedro Américo, such as Independence or Death and Batalha do Avaí, and Meirelles' own works, such as Batalha dos Guararapes, The First Mass in Brazil is part of a group of romantic representations of Brazil's history.[11] The theme of the "First Mass" has an extensive iconography in the Americas and was revisited during the Republican period in Brazil as a founding milestone of city creation. It was a way to emphasize regional stories.[2] Meirelles' work aimed to be a founding milestone not only of a specific region but of Brazil as a whole, and its widespread circulation places it as an important element of the collective imaginary of national history.[7]

As a visual representation of an event, the elements that constitute nationality in the artwork have been the subject of academic investigation. The First Mass in Brazil initially suggests that the nation was founded at the moment the Portuguese established Catholicism in the country, a characteristic that contributes to the idea of the nation's emergence from a civilizing action.[7] The harmony among the figures depicted in the painting also suggests an idea of equality and contributes to the creation of another aspect of national identity: that the construction of its symbols is a tool for containing revolts.[4]

Reception edit

After its first exhibition at the Salon de Paris in 1861, the artwork was once again exhibited abroad in May 1876. Alongside two other works by Meirelles, Passagem de Humaitá and Combate Naval de Riachuelo, The First Mass in Brazil was displayed in the Fine Arts section of the Philadelphia Exposition in the United States.[8] In addition to its reception in international exhibitions, the artwork granted Victor Meirelles the title of Imperial Knight of the Order of the Rose and the position of honorary professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.[5]

In 2013, the painting was part of the long-term exhibition Quando o Brasil Amanhecia at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro,[6] in the Gallery of 19th century Brazilian Art.[12]

Gallery edit

- Studies for the painting

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Couto, Maria de Fátima Morethy (November 4, 2009). "Imagens eloqüentes: a primeira missa no Brasil". Artcultura. 10 (17). ISSN 2178-3845.

- ^ a b c d e Christo, Maraliz de Castro Vieira (December 30, 2009). "A pintura de história no Brasil do século XIX: Panorama introdutório". Arbor. 185 (740): 1147–1168. doi:10.3989/arbor.2009.740n1082. ISSN 1988-303X.

- ^ a b Molina, Ana Heloisa (July 30, 2014). "Ensino de História e Imagens: possibilidades de pesquisa". Domínios da Imagem. 1 (1): 15–29. ISSN 2237-9126.

- ^ a b DECCA, EDGAR SALVADORI DE. "CIDADÃO, MOSTRE-ME A IDENTIDADE!" (PDF). Cad. Cedes. Unicamp. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Venâncio, Giselle Martins (June 25, 2009). "PINTANDO O BRASIL: artes plásticas e construção da identidade nacional (1816-1922)". Revista Eletrônica História em Reflexão. 2 (4). ISSN 1981-2434.

- ^ a b "Museu de Belas Artes exibe obras consideradas ícones das artes plásticas do país". EBC. April 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Venâncio, Giselle Martins (June 25, 2009). "PINTANDO O BRASIL: artes plásticas e construção da identidade nacional (1816-1922)". Revista Eletrônica História em Reflexão. 2 (4). ISSN 1981-2434.

- ^ a b c Coelho, Mario Cesar (2007). "Os Panoramas perdidos de Victor Meirelles: aventuras de um pintor acadêmico nos caminhos da modernidade". Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ Castro, Isis Pimentel de (2009). "Entre a opsis e a akôe: as marcas de enunciação na pintura histórica e na crítica de arte do oitocentos". História da Historiografia. 2 (2): 29–49. doi:10.15848/hh.v0i2.6.

- ^ Guimarães, Francisco Alfredo Morais. "A TEMÁTICA INDÍGENA NA ESCOLA: ONDE ESTÁ O ESPELHO?". Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ Coelho, Tiago da Silva (December 19, 2012). "A IMAGEM E O ENSINO DE HISTÓRIA EM TEMPOS VISUAIS". PerCursos. 13 (2): 188–199. ISSN 1984-7246.

- ^ Globo, Acervo - Jornal O. "Da Academia Real ao Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, um tesouro de 20 mil obras". Acervo.