Summary

Tey was the Great Royal Wife of Kheperkheprure Ay, who was the penultimate pharaoh of Ancient Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty. She also had been the wet nurse of Nefertiti.[1]

| Tey | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Royal Wife Eighteenth dynasty queen | ||||||

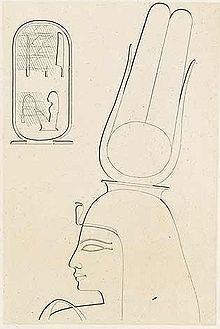

Queen Tey as depicted at the chapel at Akhmim (from Lepsius, Denkmäler) | ||||||

| Spouse | Ay | |||||

| Egyptian name |

| |||||

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty | |||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | |||||

Her husband, Ay filled important administrative roles in the courts of several pharaohs – Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamen – before ascending the throne following the death of Tutankhamen, as the male line of the royal family became extinct. He is believed to be connected to the royal family, probably a brother of Queen Tiye (wife of Amenhotep III). Some researchers theorize that he even may have been the father of Nefertiti.

Family edit

Tey was Ay's wife. In inscriptions at Amarna, Tey is called "Nurse of the Great Royal Wife." It has been theorized that this title meant she was stepmother to Nefertiti as Ay's second wife.[2] Ay and Tey are never explicitly called Nefertiti's father or mother. Thus, if Tey was Ay's only wife, neither were parent to Nefertiti.[3] However, if they are the parents of Nefertiti, Mutbenret was most likely Ay and Tey's daughter. Further, Nakhtmin, Ay's intended successor, might be their son.[4]

Additionally, Tey may have had a sister named Mutemnub and brother-in-law named Nakhtmin. On a statue currently in the Brooklyn Museum, a dignitary named Ay is called Second Prophet of Amun, high priest of Mut, and Steward of Queen Tey. His parents are recorded as Nahtmin and Mutemnub, sister of Queen Tey. The inscription is usually interpreted to mean that she was this Tey's sister.[5]

Amarna edit

Tey is depicted in her husband's unused Amarna tomb,[1] prepared while he was an administrator to Akhenaten. Her prominence in the decoration is exceptional, but her positions as nurse and tutor of the Great Wife (Nefertiti), and King's Royal Ornament fully justify it.[6] A reward scene is depicted on the North Wall, East Side. Aye and Tey are shown before the window of appearances. Akhenaten is shown in a Khepresh crown and Nefertiti in her well-known blue crown (in this case decorated with three uraei). Meritaten, Meketaten, and Ankhesenpaaten are shown in the window of appearances as well. The elder two daughters seem to be throwing rewards to Aye and Tey, while Ankhesenpaaten stands on the pillow before Nefertiti and is caressing her chin.[7]

Great Royal Wife edit

When Ay assumed the throne after the death of Tutankhamen, Tey became his Great Royal Wife and then held the titles Hereditary Princess (iryt-p`t), Great of Praises (wrt-hzwt), Lady of The Two Lands (nbt-t3wy), Great King’s Wife, his beloved (hmt-niswt-wrt meryt.f), and Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt (hnwt-Shm’w T3-mhw).[8]

Queen Tey is depicted in the tomb WV23 in the Valley of the Kings, used for Ay after he had become king. She appears behind Ay in a scene where Ay appears to be pulling lotus flowers from a marsh. The images are rather severely damaged.

Tey may have been buried with her husband in WV23. Fragments of female human bones found in the tomb may be Tey's.[9]

Tey is also depicted in a rock chapel dedicated to fertility god Min in Akhmim.[1]

Tey also is mentioned on a wooden box inscribed for "The true scribe of the king whom he loves, troop commander, overseer of cavalry, and Father of the God, Ay." The text mentions: "The much-valued one, the sole one (unique) of Re, appreciated by the Great Royal Wife, the mistress of the house, Tey."[10]

A colossal statue at Akhmim was likely carved in Tey's likeness, but was later reinscribed for Meritamen, a daughter-wife of Ramesses II.[11]

References edit

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3., p.157

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, pp.36,147

- ^ Jacobus Van Dijk, Horemheb and the Struggle for the Throne of Tutankhamun, BACE 7 (1996), p.32

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, pp.151-153

- ^ Dodson & Hilton, p.155

- ^ de Garis Davies, N. (1908). The Rock Tombs of El Amarna Volume VI: The Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu, and Ay (2004 Reprint ed.). Egypt Exploration Society. p. 21. ISBN 0-85698-161-3.

- ^ Norman De Garis Davies, The Rock Tombs of el-Amarna, Parts V and VI: Part 5 Smaller tombs and boundary stelae & Part 6 Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu and Ay, Egypt Exploration Society (2004)

- ^ Grajetzki, Ancient Egyptian Queens: a hieroglyphic dictionary, Golden House Publications. p.63-64

- ^ J. Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, 2006, Thames & Hudson

- ^ Roeder, G.: Aegyptische Inschriften aus den Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. - Bd.II - Leipzig: 1924. - p.267-268

- ^ Dodson, Aiden (2009). Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-61797-050-4.