Summary

| Siege of Pondicherry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War[1] | |||||||

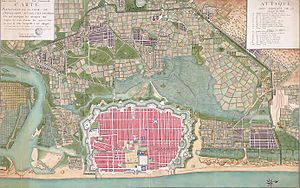

French map depicting the siege, c. 1778 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hector Munro Edward Vernon |

Guillaume de Bellecombe (POW) François-Jean-Baptiste l'Ollivier de Tronjoli | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,500 British army regulars 9,000 or more company troops and sepoys |

700 French regulars 400–600 sepoys | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

77 British army killed 11 British navy killed 155 sepoys killed 193 British army wounded 53 British navy wounded 684 sepoys wounded |

92 French killed 52 sepoys killed 191 French wounded 94 sepoys wounded | ||||||

class=notpageimage| Location within Puducherry Siege of Pondicherry (1778) (India) | |||||||

The siege of Pondicherry was the first military action on the Indian subcontinent following the declaration of war between Great Britain and France in the American Revolutionary War. A British force besieged the French-controlled port of Pondicherry (now Puducherry) in August 1778, which capitulated after ten weeks of siege.

Background edit

Following the colonial victory at Saratoga in October 1777, France decided to declare war on Great Britain as an ally to the United States. Word first reached the French Indian colony of Pondicherry in July 1778 that France and Britain had recalled their ambassadors, a sign that war was imminent. The British colonies had already received orders to seize the French possessions in India and begun military preparations.

French defenses edit

Pondicherry was the capital of French India and the largest of France's possessions on the subcontinent. The British would capture all of the other possessions without resistance in 1778; only Pondicherry was actively defended. The French governor, General Guillaume de Bellecombe, had at his disposal about 700 French troops and 400 sepoys (local Indian troops), and a city whose fortifications were in some disrepair. Pondicherry, as was the case with a number of other European colonial outposts in India, changed hands due to military action several times in the colonial period. Attempts to significantly improve its defences after the last round of battles in the Seven Years' War were frustrated by political infighting in the French colonial administration. In 1778 the outer works of the city were largely incomplete, with significant elements unfinished and parts of the city exposed to direct attack.

Bellecombe immediately set about improving the defences, working as quickly as possible in anticipation of British movements. Key gates were blocked, stockades and gun batteries were constructed along the shore, and anything that might give cover to the British on their advance on the defences was removed or destroyed. Bellecombe also received additional troops before the British arrived. The garrison from Karikal (which the British occupied on 10 August) add about 100 sepoys to the defence, and some of Pondicherry's inhabitants also took up arms.

A small French navy was assembled to counteract the small British navy. Admiral Tronjoli took command of the 64-gun ship of the line Brillant, the frigate Pourvoyeuse and three smaller ships, Sartine, Lawriston, and Brisson.[Note 1]

The siege edit

Preliminaries edit

The British colonial administration in Madras placed General Hector Munro in command of an army of nearly 20,000 men, which began arriving within a few miles of Pondicherry on 8 August. By 20 August the full army had arrived, the city was surrounded, and siege operations began.

The first noteworthy exchange between the forces was a naval encounter. Admiral Edward Vernon's fleet also consisted of five ships, carrying slightly less firepower than the French fleet. Vernon commanded the 60-gun ship of the line HMS Rippon, and was assisted by HMS Coventry, HMS Seahorse, HMS Cormorant, and the East India Company's ship Valentine.

In a largely inconsequential two-hour engagement in which Tronjoli was wounded, the French fleet drove Vernon away on 10 August. On 14 August French ships spotted two unknown sails; they were transport ships of the British East India Company. Their captains, apparently unaware of the hostilities, sailed before Pondicherry with British flags flying. Two of the French fleet, Pourvoyeuse and Sartine lazily gave chase. The British merchant ships escaped, but Sartine was captured when she strayed too close to the British squadron on 25 August.[5][Note 2] The loss of parity between the navies was partially made up by the arrival at Pondicherry of the 26-gun frigate Elizabeth, another private ship that had been pressed into service in the French fleet.[Note 3]

On 20 August, the British fleet, now six ships, appeared again. The French fleet, although it had been augmented by Elizabeth, was forced to leave Le Brisson in the harbour due to damage sustained in the first engagement, and was thus at a disadvantage. The next day, Tronjoli sailed the rest of the fleet south. Sources disagree on whether or not battle was offered or attempted on either side, but apparently no battle took place, and Tronjoli continued south. Bellecombe was surprised and dismayed to learn on 2 September that Tronjoli had sailed for Île de France, leaving Elizabeth and La Pourvoyeuse behind.

The British troops were not noticeably active in their siege operations until September. Bellecombe used the remaining time to further strengthen the defences, constructing more dikes and iron-cladding the powder magazine. He also repeatedly had to stop the ineffective fire of cannon at the distant British positions.

Siege operations edit

On the night of 1 September the British advanced a force of about 300 as cover for engineers to begin siege operations. Two positions were identified for attack; the northwest bastion, and the southernmost bastion. Batteries were established to cover this work, and a third battery was placed to the southwest on 3 September that was positioned to enfilade the French defences. Bellecombe's response was to send out a few hundred men to feint an attack on the southern battery. This drew nearly 3,000 British troops within reach of the French guns, which inflicted significant damage with only a single French death.

The British siege operation proceeded throughout September, often under heavy fire. British batteries moved progressively closer to the walls, inflicting heavy damage within the city. The hospital had to be evacuated, and the powder magazine (a particular target of the British guns) was also emptied. On 19 September a British cannonball killed the commander of the French artillery. By 24 September breaches were beginning to show in the bastions under attack, and by 6 October the British trenches had reached the inner ditches, with additional gun batteries doing significant damage along the entire French works.

On 25 September the French attempted a nighttime sortie to destroy the southern battery. The effort was abandoned when secrecy was lost (a sentry was disarmed but not killed, so he was able to raise the alarm) and when the company lost its way. A second sortie on 4 October was a little more successful. The southwest gun battery was reached while its crew was asleep; the guns were spiked (albeit poorly enough that they were soon back in service), and some of the crew were slaughtered. Bellecombe also received a minor injury after a musket ball struck him on 4 October, but was able to continue leading the defence.

Siege ends edit

Between 6 and 13 October, the British siege operations continued, but heavy rains hampered them. The British succeeded in draining the northern ditch, which the French unsuccessfully attempted again to flood. On 14 October the walls of the two bastions the British had targeted lay in ruins, and preparations began for an assault.

Bellecombe was also running out of ammunition. After holding a war council on 15 October, he sent a truce flag to Munro the next day. He signed the terms of capitulation on 18 October.

Aftermath edit

The French force of less than 1,500 had withstood a siege of nearly eighty days by a British force that numbered 20,000. The defenders' losses were high: more than 300 French and nearly 150 sepoy casualties, along with more than 200 civilian casualties. The British suffered more than 900 casualties. The French defenders were allowed to march out with full colours, and were eventually returned to France.

Britain followed up the victory by seizing France's other Indian colonies, contributing to the outbreak of the Second Mysore War.

Footnotes edit

- Notes

- ^ All three were merchant vessels, pressed into service. Sartine was armed with twenty-six 8-pounder guns.[2] Lauriston (or Lawriston or L'Oriston), had been built at Rangoon, was of 1000 tons, and was armed with 22 or 26 guns. She was returned to merchant service in June 1781 at Île de France but again requisitioned in December 1781. the British captured her in February 1782.[3] Brisson was a merchant vessel of about 650–700 tons and twenty 8-pounder guns that the French requisitioned in July 1778 for the defense of Pondicherry.[4]

- ^ The Royal Navy took Sartine into service as the fifth-rate frigate HMS Sartine. The prize money notice for the capture of Sartine mentions the four Royal Navy vessels but does not mention Valentine. Vernon had sent her off to carry dispatches after the battle.[5]

- ^ Elizabeth, of 800 tons, was armed with 24 guns and 10 swivel guns. In 1779 she was reported to be an armed transport at Brest.[6]

- Citations

References edit

- Barras, Paul (1895). Duruy, George (ed.). Memoirs of Barras, member of the directorate, Volume 1. Translated by Roche, Charles Émile. Harper Brothers.

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine de Louis XVI: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1774 à 1792 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-906381-23-3.

- Tucker, Spencer (2018). American Revolution: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851097449.

- Marshman, John Clark (1867). The history of India, Volume 1. Harrison. OCLC 41875959.

Mahe capture 1781.

- The Military History of the Madras Engineers and Pioneers. 1881.

- The Universal Magazine. 1779. (includes British reports back to London following the siege)

Further reading edit

- Bellecombe's account (in French). 1905.