Summary

Michael B. Hancock (born July 29, 1969)[1] is an American author and politician who served as the 45th mayor of Denver, Colorado from 2011 to 2023. A member of the Democratic Party, he was in his second term as the Denver City Councilor from the 11th district at the time he was elected to the mayorship.

Michael Hancock | |

|---|---|

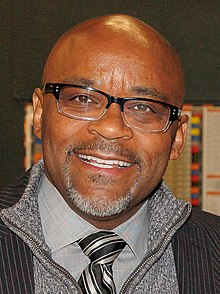

Hancock in 2022 | |

| 45th Mayor of Denver | |

| In office July 18, 2011 – July 17, 2023 | |

| Preceded by | Bill Vidal |

| Succeeded by | Mike Johnston |

| Member of the Denver City Council from the 11th district | |

| In office July 21, 2003 – July 18, 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Jon Bowman |

| Succeeded by | Unknown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 29, 1969 Killeen, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Hastings College (BA) University of Colorado, Denver (MPA) |

| Website | Campaign website |

During his tenure on the Denver City Council from July 20, 2003, to July 18, 2011, Hancock served two terms as the body's president, the last ending in 2008. He was sworn in as Mayor of Denver on July 18, 2011, after defeating Chris Romer in a runoff election on June 7, 2011.[2][3] Easily reelected with no significant opposition in 2015,[4] Hancock was reelected to a third and final term in 2019. He was Denver's second African American mayor after Wellington Webb.

Biography edit

Born at Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas, Hancock moved with his family to Denver as an infant. He and his twin sister are the youngest of ten children.[5] According to a DNA analysis performed on his behalf, he descends mainly from enslaved Cameroonians.[6]

During the 1986 Denver Broncos Super Bowl season, while in high school, Hancock performed as the Broncos's mascot "Huddles", making $25 an hour.[7] Hancock graduated from Denver's Manual High School (1987) and earned a bachelor's degree in political science from Hastings College in Nebraska (1991). He also earned a Masters of Arts degree in public administration management from the University of Colorado Denver.[5][8][9][10][11]

Hancock and former Colorado State Senator Peter Groff co-wrote the book Standing in the Gap: Leadership for the 21st Century,[12] published in 2004. On May 8, 2012, Hancock visited the city of Reykjavík and met the Mayor of Reykjavík, Jón Gnarr, in Höfði.[13] Hancock was named a 2014 Aspen Institute Rodel Fellow.[14]

Hancock is married to actress and vocalist Mary Louise Lee. They have three children. In April 2021 the couple announced their separation and that they will file for divorce.[15] Hancock serves as a deacon at the New Hope Baptist Church.[16]

Professional life edit

Hancock started his career in the early 1990s, holding down two jobs at the Denver Housing Authority and the National Civic League — while also pursuing a master's degree.

At the Housing Authority, he designed, implemented, and oversaw the first-ever athletic, cultural and leadership-training programs for 11,000 inner-city kids living in public housing. Hancock also helped write a state law outlawing drug possession within 100 feet of public housing.

With the National Civic League, Hancock helped communities, nonprofits, and other clients all over the country craft and enact strategic plans to solve economic and budget challenges, increase civic participation and improve governance.

He joined the Metro Denver's Urban League affiliate in 1995 as program director at a time when the economic-empowerment and civil rights organization was struggling — struggling so much that his first paycheck bounced.[citation needed] Undaunted, Hancock rose through the ranks, developing a strategic plan, overseeing day-to-day operations and leading fundraising efforts. He became Executive Vice President, interim President, and then President in 1999.

At 29 years old, Hancock was the youngest leader of an Urban League chapter anywhere in the United States. He developed a talented staff, created a nationally recognized and award-winning job training program, and built private sector partnerships with companies like Qwest, Comcast, and AT&T.

Denver City Council edit

After almost five years as President of Metro Denver Urban League, Hancock stepped down in 2003 when voters in northeast Denver's 11th district elected him to the Denver City Council. He was reelected in 2007. His council peers unanimously chose him to serve two terms as President of the Denver City Council from 2006 to 2008. He presided over the creation of the Denver Pre-School Initiative, strategies to fight foreclosures, as well as the implementation of the largest infrastructure improvement in Denver history.

While on the Denver City Council, Hancock was a leader on neighborhood issues, citywide finances, economic development and children's issues.

Mayor of Denver edit

Mayor John Hickenlooper was elected governor of Colorado in the 2010 elections In the May 3, 2011, first primary for Denver mayor, Hancock was among the final two finishers against State Senator Chris Romer. Romer led the first round with 31,901 votes (28.49%) to Hancock's 30,314 votes (27.04%). Hancock went on to defeat Romer in the June 7, 2011 Runoff election in a landslide with 70,780 votes (58.08%) to Romer's 51,082 votes (41.92%). Hancock was inaugurated as the 45th Mayor of Denver on July 18, 2011.

Hancock was reelected on May 5, 2015, in a landslide victory with 75,774 votes (80.16%) against Marcus Giavanni, who pulled a second place win with 8,033 votes (8.50%). There were no mayoral debates in 2015. Hancock was inaugurated on July 20, 2015, at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House. In May 2018, it was reported Hancock was outraised by entrepreneur Kayvan Khalatbari for his upcoming reelection bid in the first reporting quarter of the year.[17]

In June 2019, Hancock was nevertheless reelected with 56.3% of the vote in a runoff from the May 2019 general election in which Hancock and Jamie Giellis were the top two finishers. Giellis received 43.7% of the votes in the June 4 runoff.[18]

In 2020, Hancock came out in favor of reparations for slavery in the United States. He created a Black Reparations Fund at the Denver Foundation, which collects donations to be eventually distributed to the city's Black residents.[19] In June 2021, Hancock was one of 11 U.S. mayors who formed Mayors Organized for Reparations and Equity (MORE), a coalition of municipal leaders dedicated to starting pilot reparations programs in their cities. Hancock is co-chair of MORE, along with Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti.[19]

In April 2022, on behalf of the city of Denver, Hancock formally apologized for the anti-Chinese race riots that occurred in 1880. He gifted the descendants of the victims a commemorative token and a signed apology letter. The apology letter stated that the city of Denver would build an Asian Pacific District, partner with the education system to have a program on Asian Pacific Coloradans, and an Asian Pacific American Community Museum.[20]

Controversies edit

In 2012, political activists Occupy Denver opposed legislation Mayor Hancock signed banning unauthorized camping; critics said it criminalized homelessness.[21][22] Hancock has also drawn international attention for his oppositional positions towards the city's homeless residents, including threats from Anonymous in 2016 to expose alleged ties to an escort service.[23]

In 2016, following a speech on poverty and hope through low-income housing, his police force cracked down on the residents, which Denver Homeless Out Loud livestreamed officials partaking in sweeps.[24]

The ACLU of Colorado issued oppositional statements toward the mayor's office for the misuse of appropriations designed to help the homeless, instead used to evict them.[25] As winter approached, the police force was condemned by the organization for confiscating the bedding materials of the residents.[26]

Housing controversy edit

In 2018, it was reported the city's affordable housing program permitted overqualified purchasers, resulting in the loss of compliance for the program from the Land Title Association of Colorado.[27][28]

Sexual harassment case edit

Hancock admitted to sending suggestive text messages to his female subordinate, Leslie Branch-Wise, during his first year as mayor.[29] He acknowledged his behavior as "inappropriate" when the victim, a Denver Police Department Detective, gave an interview in 2018 to disclose the sexual harassment she experienced. By providing several suggestive text messages from Hancock, the detective provided a glimpse into the suffering she encountered during the time she worked for Hancock's security detail in 2012. Following the Detective's interview, Hancock issued a blanket public apology to the victim, his family and the people of Denver. Hancock explained, "I made a mistake. I'm human. I never purport to be perfect." He called the circumstances "wrought with politics" and concluded: "It was just one of those things where I got too casual and too familiar, and I learned a lesson from that."[30] The city paid the officer $75,000 as part of a settlement.[29]

Son's body camera video with police edit

On March 23, 2018, Mayor Hancock's 22-year-old son, Jordan Hancock, was pulled over by Aurora Police for going 65 mph in a 40 mph zone.[31] In August, body camera footage was released of the incident; in the video, he can be seen and heard berating the Aurora Police officer who pulled him over. He uttered homophobic slurs, cursed at the officer, insulted the officer and threatened his job.[32] The officer remained calm and courteous and issued him the citation. It was revealed that Jordan Hancock was ordered to pay a $275 fine for his speeding that day and Mayor Hancock has claimed that his son would apologize to the officer in person one day if given the opportunity.[33]

Other decisions edit

In February 2020, Mayor Hancock's first veto in his three terms of office was to strike down the repeal of the three-decades old pit bull breed ban in Denver.[34]

In November 2020, Hancock told his constituents to stay home and stay safe from COVID-19 during Thanksgiving in 2020; however, he ignored his own advice and was caught flying on a commercial flight to Mississippi to visit family.[35]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "Michael Hancock - Elections Colorado Profile". Denver Post.

- ^ Meyer, Jeremy P. (July 18, 2011). "Michael Hancock is sworn in as Denver's 45th Mayor". Denver Post. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ "Michael Hancock wins Denver Mayoral runoff election". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- ^ Jon Murray (May 5, 2015). "Denver Mayor Michael Hancock coasts to re-election; surprise in auditor's race". Denver Post. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ a b About Counc. Michael B. Hancock Archived July 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cameroonian-Americans Discover Ancestry Lost in Slave Trade Posted by Irene Zih Fon, Reporter. Archived May 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "That time Denver Mayor Michael Hancock was Broncos’ mascot Huddles," Denver Post (February 4, 2016).

- ^ Michael Booth (April 7, 2011). "Denver mayoral candidate profile: Michael Hancock running on reputation, enthusiasm". Denver Post. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ "Michael Hancock's Bio". 7NEWS. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ "Hastings College announces graduating class". Scottsbluff Star-Herald. June 2, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

The Honorable Michael B. Hancock, mayor of Denver and a 1991 Hastings College alumnus, challenged HC's 126th graduating class to be themselves, even if that means being out of step with others.

- ^ "Hancock for Denver – About Michael". hancockfordenver.com. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

Michael is a graduate of Manual High School (Class of 1987), where he served as class president and played wide receiver and safety for the Manual Thunderbolts.

- ^ Standing in the Gap: Leadership for the 21st Century

- ^ "Icelandair Flight Strengthens Iceland's Ties with Colorado". Iceland Review. May 9, 2012.

- ^ "Hodges begins national leadership program in Colorado". MinnPost. January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

Others, besides Hodges and Mack, in this, the tenth Rodel Fellowship class:... Denver Mayor Michael Hancock

- ^ "Mayor Hancock, first lady announce their separation". April 30, 2021.

- ^ Michael Hancock running on reputation, enthusiasm', Michael Booth. Denver Post. April 6, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2018

- ^ "Denver Mayor Michael Hancock’s campaign donors didn’t stay away amid scandal, but he raised less than challenger", Jon Murray. Denver Post. April 17, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018

- ^ "Mayoral election in Denver, Colorado (2019)", Ballotpedia.org. Retrieved February 14, 2020

- ^ a b Metzger, Hannah. "Denver Mayor Hancock leading national reparations effort for African Americans," Denver Gazette (July 25, 2021).

- ^ "Denver officially apologizes for 1880 anti-Chinese race riot". RMPBS. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Occupy Denver Writes Open Letter To Denver Mayor Hancock Over Urban Camping Ban", Occupy Denver General Assembly. Huffington Post. April 9, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ "Denver City Council votes 9-4 to ban homeless camping", Jeremy P. Meyer. Denver Post. May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2018

- ^ "Anonymous to Michael Hancock: Resign or We'll Expose Your Tie to Prostitution Ring", Michael Roberts. Westword. May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ "Crackdowns on homeless camps follow Hancock’s ‘State of the City’ speech", Eliza Carter, Colorado Independent. July 21, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016

- ^ "ACLU Demands Accountability for Denver’s Misuse of Donated Funds to Pay for Homeless Sweeps", ACLU of Colorado. July 6, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016

- ^ "ACLU to Denver Police: Stop Taking Blankets from Homeless People", ACLU of Colorado. December 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2018

- ^ "Denver affordable housing controversy: Mayor won’t say if homeowners could be forced to sell", Rob Low. KDVR. April 2, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018

- ^ "After affordable housing debacle, title industry rebuffs Denver’s request to ensure compliance with program rules", Aldo Svaldi. Denver Post. April 20, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018

- ^ a b Wootson, Cleve R. Jr. (May 8, 2018). "'My dad's the mayor!': Leaked video shows Denver official's son cursing at officer during stop". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ^ Murray, Jon; Kovalesky, Tony (February 27, 2018). "Denver mayor admits he sent suggestive text messages to police officer in 2012". Denver Post. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ "Body camera video released of Denver mayor's son threatening officer". FOX31 Denver. August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Joyce, Kathleen (August 17, 2018). "Police release body camera footage of Denver mayor's son's expletive-laden outburst at cop". Fox News. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Miller, Tony Kovaleski, Blair (August 16, 2018). "New body cam video details explicit exchange between Denver mayor's son and Aurora traffic officer". 7NEWS. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "No repeal of Denver pit bull ban after all: Mayor to veto council decision". The Denver Post. February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Denver mayor traveled for Thanksgiving despite pandemic and Twitter was not happy about it". The Denver Post. November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

External links edit

- Campaign website

- City Council website for District 11

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "America’s 11 Most Interesting Mayors" from Politico magazine