Summary

Fructuosus of Braga (? – 16 April 665),[1] was the Bishop of Dumio and Archbishop of Braga, also known for being a great founder of monasteries The son of a Visigothic dux in the region of Bierzo, at a young age he accompanied his father on official trips over his estates. After a period spent as a hermit, he established a monastery at Complutum and became its first abbot.

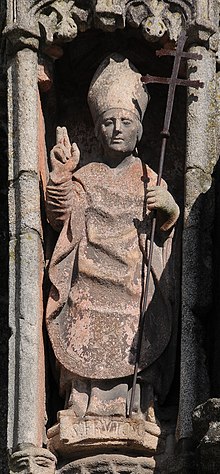

Saint Fructuosus of Braga | |

|---|---|

Statue of Fructuosus on a façade of Braga Cathedral | |

| Bishop Confessor | |

| Born | last decade of 6th century or early 7th century El Bierzo or Toledo, Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania |

| Died | 16 April 665 Braga (present-day Portugal) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Feast | 16 April |

| Attributes | Monk with a stag |

Life edit

After the death of his parents, Fructuosus first sought instruction from the Bishop of Palencia[2] before retiring as a hermit to a desert in Galicia. Many pupils gathered around him, and thus originated the monastery of Complutum in the El Bierzo region, over which he himself at first presided, later, he appointed an abbot and again retired into the desert. In the course of time, he founded nine other monasteries, including one for women under the abbess Benedicta.[3]

Abbot edit

Some of these were located in Gallaecia, but he subsequently established monasteries farther south in the Iberian Peninsula.[4] The location of these foundations "is not known with complete certainty."[4] Fructuosus established Rufiana or the Monasterium Rufianense[5] in El Bierzo, as well as a monastery known as Visoniense and another known as Peonense.[4] It has been speculated[4] that these may refer to San Pedro de Montes, San Fiz de Visoña, San Juan de Poyo, respectively. In Baetica, he established a monastery at the Island of Cádiz and a nunnery called Nono, as it was established nine miles from the sea.[6]

His monastery at Compludo was known for its unusually severe Rule. In this monastery, monks were required to reveal all their thoughts, visions and dreams to their superiors. They were subjected to bedtime inspections throughout the night. Monks were forbidden to look at each other. Punishments here were also unusually harsh and included flogging and imprisonment within the monastery on a diet of six ounces of bread for three to six months.[7]

His relationship with the kings of his time was not always a happy one. In 652, he wrote what was apparently a second letter to King Recceswinth asking for the release of political prisoners held from the reign of King Chintila, some of whom had languished in prison until the reign of King Erwig.

Bishop edit

He was later present at the Eighth Council of Toledo in 653, in place of Bishop Riccimer of Dumio. It was at this council that Fructuosus raised the issue of political prisoners once again. After the death of Bishop Riccimer, Fructuosus succeeded him in the See of Dumio in 654. In 656, he undertook to plan for a voyage to the Levant. However, according to the new laws enacted by King Chindasvinth, it was illegal to leave the kingdom without royal permission. One of the few disciples privy to his plans had given him up to authorities and Fructuosus was subsequently arrested and imprisoned.

Fructuosus attended the Tenth Council of Toledo in December 656. The last will and testament of the recently deceased bishop Riccimer, was disputed by those who saw his freeing of slaves and distribution of church rents to the poor was responsible for the subsequent impoverishment of that see. The council agreed that, by not providing compensation, Riccimer had obviated his duty and the acts of his will were rendered invalid. They gave the job of correcting the problem to Fructuosus and commanded him to take moderation in the case of the slaves. At the same council, Archbishop Potamius of Braga was remanded to a monastery for licentiousness and his archdiocese was given to Fructuosus on 1 December 656.[8]

Fructuosus dressed so poorly as to be mistaken for a slave and he even received a beating from a peasant, from which he was only saved by a miracle (according to the monastic chroniclers). His Vita is one of the chief sources for writing the history of his age. From the 16th to the mid 20th century the authorship of the Vita Fructuosi was wrongly attributed to Valerio of Bierzo.[9] It is now accepted to have been written by an anonymous monastic disciple.[10]

The feast day of Saint Fructuosus is observed on 16 April. His relics, which for a time were in the Cathedral of Braga, were later transferred to the Shrine of Santiago de Compostela in the year 1102. They were returned to their original location in 1966. Fructuosus is depicted with a stag, which was devoted to him, because he had saved it from hunters.[3]

Notes edit

- ^ Like many such accounts, his vita is clear on the day but hazy on the year.

- ^ Monks of Ramsgate. “Fructuosus”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 17 April 2013 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Meier, Gabriel. "St. Fructuosus of Braga." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 27 January 2019 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d María Adelaida Andrés Sanz; Carmen Codoñer Merino; La Hispania Visigótica y Mozárabe: Dos épocas en su Literatura. Volume 28. Universidad de Salamanca, 2010), pg. 121. ISBN 9788478001729

- ^ Ulick Ralph Burke, A History of Spain: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Ferdinand the Catholic, Volume 1. (Longmans, Green, 1900), p. 106. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Butler, Alban. “Saint Fructuosus, Archbishop of Braga, Confessor”. Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info. 15 April 2013 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Roger Collins, Early Medieval Spain. (New York: St Martin's Press, 1995), p. 84.

- ^ Karl Joseph von Hefele (1895). A History of the Councils of the Church: From the Original Documents. Vol. IV. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 474–475. J.-D. Mansi (ed.), Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, editio novissima, Tomus XI (Florence: A. Zatta 1765), pp. 40-41, 43.

- ^ Francis Clark, (2003), The "Gregorian" dialogues and the origins of Benedictine monasticism, page 353. BRILL

- ^ Roger Collins, (2004), Visigothic Spain, 409-711, p. 170. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.

Sources edit

- Thompson, E.A. The Goths in Spain. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1969.

- Iberian Fathers. Writings of Braulio of Saragossa, Fructuosus of Braga, translated by Claude W. Barlow Catholic University of America Press (1969).