Summary

On June 23, 2016, a flood hit areas of the U.S. state of West Virginia and nearby parts of Virginia, resulting in 23 deaths. The flooding was the result of 8 to 10 inches (200 to 250 mm) of rain falling over a period of 12 hours, resulting in a flood that was among the deadliest in West Virginia history.[3] It is also the deadliest flash flood event in the United States since the 2010 Tennessee floods.[4]

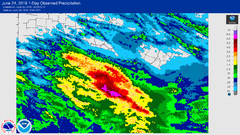

Rainfall accumulations across West Virginia from 8:00 a.m. on June 23 to 8:00 a.m. on June 24 (12:00–12:00 UTC) | |

| Date | June 23–24, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Location | West Virginia and Virginia, United States |

| Deaths | At least 23[1] |

| Property damage | $1.1 billion (2016 USD)[2] |

Flood event edit

On June 23, 2016, thunderstorms brought torrential rain to much of West Virginia, resulting in accumulations of up to 10 in (250 mm) in 12–24 hours. According to meteorologists at the National Weather Service, this rainfall qualifies as a 1,000 year event for parts of Kanawha, Fayette, Nicholas, Summers and Greenbrier counties[citation needed]. Rainfall totals included 9.37 in (238 mm) in Maxwelton and 7.53 in (191 mm) in Rainelle.[5] Two-day accumulations in White Sulphur Springs reached 9.17 in (233 mm).[6] In addition to the torrential rain, the storms produced an EF1 tornado near Kenna in Jackson County. The brief tornado lifted and rolled a single-wide trailer, injuring its two occupants; minor damage occurred elsewhere along its path.[7]

The tremendous rainfall produced widespread and destructive flash floods in the state. The Elk River rose to an all-time high of 33.37 ft (10.17 m), surpassing the previous record of 32 ft (9.8 m) set in 1888.[8] Greenbrier County was the hardest-hit, with at least 15 deaths confirmed.[1] Greenbrier County Sheriff Jan Cahill described the county as "complete chaos".[8] Flooding in White Sulphur Springs destroyed many homes and swept some clean off their foundations.[9] One home was videotaped floating down Howard's Creek while engulfed in flames.[8] The town of Rainelle was especially hard hit, and was described as looking like "a war zone".[10][11]

Many people lost everything, and some people lost their lives.... We’re going to need some real help. This is our Katrina.

— Kanawha County Commission president Kent Carper[12]

In Kanawha County, heavy rains washed out a bridge leading to a shopping center near Interstate 79 in Elkview, stranding approximately 500 people for nearly 24 hours.[13] A 47-year-old woman drowned near Clendenin when rising waters from Wills Creek overcame her car. Despite numerous attempts, emergency responders were unable to reach her before her vehicle was swept away. Three other deaths took place near Clendenin, including a hospice patient who drowned after rescuers could not reach her home.[6] At least six people died in Kanawha County.[14]

A 4-year-old boy drowned in Ravenswood, Jackson County, after he was swept away by a swollen creek;[9] the creek, normally only ankle-deep, had risen to 6 ft (1.8 m) due to the rain.[15] An 8-year-old boy drowned in Big Wheeling Creek in Ohio County.[16]

About 500 homes were severely damaged or destroyed in Roane County.[17] In Clay County, the communities of Procious, Camp Creek and others were left in ruins.[18]

At least 60 roads were shut down, many of them swept away. Multiple bridges across the state were destroyed. In Nicholas County, the Cherry River flooded much of Richwood, forcing the evacuation of a nursing home.[5][8] Homes in low-lying areas of the county were flooded up to the roof.[12] Electric utilities reported at one point that 500,000 customers were left without power from the floods.[9]

Record-high and near-record-high waters were reported along the Greenbrier River at Hilldale (25.9 ft (7.9 m) over flood stage) and Ronceverte (23.3 ft (7.1 m) over flood stage), as well as along the New River at Thurmond (19.3 ft (5.9 m) over flood stage). Summersville Lake increased by 43.5 billion gallons between 8 am June 23 and noon June 24.[19]

On June 27, it was announced that two people on a camping trip in Greenbrier County, who were thought to have been swept away in a camper and presumed dead in the flooding, had been found alive.[20]

Aftermath edit

| County | Deaths | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Greenbrier | 15 |

[1] |

| Kanawha | 6 |

[14] |

| Jackson | 1 |

[6] |

| Ohio | 1 |

[6] |

| Total | 23 | [1] |

In the wake of the floods, West Virginia Governor Earl Ray Tomblin declared a state of emergency for 44 of the state's 55 counties.[8] He also ordered the deployment of 400 members of the West Virginia National Guard. Search and rescue teams were deployed across the state to assist stranded residents.[14] Numerous swift water and rooftop rescues were conducted.[9] A volunteer firefighter and other residents of White Sulphur Springs used front-end loaders and other heavy machinery to move through debris-laden floodwaters during the overnight of June 23–24 to save 60 people.[15] On June 25, President Barack Obama declared West Virginia a major disaster area, ordering aid to assist victims of the floods in Kanawha, Greenbrier and Nicholas counties.[14] On June 28, Tomblin requested the disaster area be expanded to include Clay, Fayette, Monroe, Pocahontas, Roane, Summers and Webster counties.[21] Five of those counties — Clay, Fayette, Monroe, Roane and Summers — were granted the request.[22]

As a precautionary measure, natural gas service was suspended for White Sulphur Springs in Greenbrier County.[9]

In Fayette County, where there were reports of looters, the sheriff warned would-be thieves that citizens were legally armed and ready to protect what they had left.[23] Law enforcement officials in the county later clarified that such actions were "not sanctioned by the sheriff's department."[24]

In unaffected parts of the state including Morgantown[25] and Martinsburg,[26] residents collected items to donate to the flood-ravaged areas.

The 2016 Greenbrier Classic golf tournament, scheduled to start on July 7, was canceled due to the floods. The Greenbrier Resort, where the tournament is played, was closed indefinitely,[14][27] though available rooms were offered free-of-charge to flood victims in need of shelter.[28] By June 28, about 200 people displaced by the flood were staying at the resort.[29]

Flooding in Alleghany County, Virginia, prompted deployment of the Virginia National Guard.[30]

Impact on resiliency and flood preparedness efforts edit

The National Weather Service has described the magnitude and intensity of the June 2016 rain as a "once in 1,000 years" event. Over 10 inches of rain fell, much of it within 12 to 18 hours.[31] A 2018 report by FEMA on lessons learned suggests that this sort of rain event and flooding may occur more frequently than has previously been expected.[32]

One scientist from West Virginia University who concurs with these conclusions has emphasized the importance of "honest conversations about climate change and what it means for West Virginia" in order to prepare for more intense precipitation events.[31]

The West Virginia State Resiliency Office was created in response to the disaster. In January 2020, the office was described as "barely functioning," and rebuilding from the flood remained incomplete.[31]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d "Gianato: death total from WV flood reduced". West Virginia MetroNews. June 27, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Events". NOAA. February 2022. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Kite, J. Steven (August 17, 2016). "Deadliest Floods in West Virginia History, Ranked by Fatalities" (PDF).

- ^ Sterling, John; Fawzy, Farida; Imam, Jarim (June 25, 2016). "At least 26 dead in West Virginia flooding". CNN. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Video: Burning house floats down Howard's Creek in White Sulphur Springs". West Virginia MetroNews. June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Beck, Erin; Kersey, Lori (June 24, 2016). "At least 22 confirmed dead in massive WV flooding". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Tornado Confirmed Near Kenna in Jackson County West Virginia. National Weather Service Office in Charleston, West Virginia (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 24, 2016. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Doug Stanglin; Doyle Rice (June 25, 2016). "At least 26 dead as historic floods sweep West Virginia". USA Today. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Ortiz, Erik; Federico-O'Murchu, Sean; Varela, Jay; Rappaport, Ben. "West Virginia Floods: 23 Killed, Including Toddler, as Thousands Left Without Power". NBC News. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Wiederspiel, Alex (June 25, 2016). "Rainelle natives and mayor uncertain of what's next after flash flood". West Virginia MetroNews. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Trooper: Flood-damaged West Virginia "looks like a war zone"". CBS News. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Kris Maher (June 25, 2016). "Residents Begin Cleanup, Seek Help After Deadly West Virginia Flood". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "People at the Elkview Shopping Center can now retrieve their cars". WOWK. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e David Bailey (June 25, 2016). "West Virginia's worst flooding in a century kills 24". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Jonathan Mattise; Bruce Schreiner; Claire Galofaro (June 25, 2016). "Crews rescue the stranded in West Virginia flooding; 23 dead". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Police Find Body of Child Who Fell into Big Wheeling Creek". The Intelligencer and Wheeling News Register. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Michael Edison Hayden (June 26, 2016). "West Virginia Comes Together in Wake of Devastating Flood". ABC News. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Sean DeLancy (June 26, 2016). "Clay County devastated by flooding, in desperate need of donations". WCHS. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Sarah Plummer. "Record high waters begin to recede". The Register-Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey Morris (June 27, 2016). "Death total from West Virginia floods lowered to 23 after two presumed dead found alive". WCHS. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Gov. Tomblin expands FEMA assistance requests to seven additional counties". WOWK. June 28, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ^ "FEMA Expands Funding to 3 More Flood-Ravaged W. Va. Counties, Bringing Total to 8". ABC News. June 29, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Alex Wiederspiel (June 26, 2016). "Fayette County Sheriff's Office warns of looters in hard hit towns". West Virginia MetroNews. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Erin Beck (June 28, 2016). "Police respond to reports of armed citizen patrols". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Dave Wilson (June 25, 2016). "Local residents rallying for flood victims". WAJR. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Emily Daniels (June 25, 2016). "Community supports relief effort". The Journal. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Kalland, Robby (June 25, 2016). "Greenbrier Classic canceled due to extreme flooding in West Virginia". CBS Sports.

- ^ Todd Ward (June 25, 2016). "The Greenbrier Offers Rooms For Flood Victims". WOAY. Archived from the original on June 27, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Carlee Lammers (June 28, 2016). "Greenbrier resort opens doors for area flood victims". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Virginia National Guard assists flood response operations". WHSV. June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c Peterson, Erica (January 27, 2020). "W.Va.'s Resiliency Office Is Barely Functioning". 89.3 WFPL News Louisville. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "FEMA Region III Report: Understanding Flood Dangers in Central West Virginia". Federal Emergency Management Agency. July 23, 2018. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

External links edit

- UPDATE: Clendenin residents describe 'whole town underwater'

- Deadliest Floods in West Virginia History, Ranked by Fatalities, posted 5 August 2016 by J. Steven Kite, West Virginia University Department of Geology & Geography. [1]